The sign on the glᴀss door read “Bright Future Autism Therapy Center.” It sat in a suburban medical complex in Minneapolis, surrounded by other legitimate providers—dentists, urgent care clinics, physical therapists. On paper, Bright Future was thriving. State Medicaid billing records showed it was treating more than 200 children a day, submitting millions of dollars in claims each month for intensive behavioral therapy.

But when FBI surveillance teams parked across the street and began observing the building, something didn’t add up.

For three consecutive days, agents reported no activity consistent with a functioning clinic. No parents carrying toddlers. No therapists entering with clipboards or therapy kits. No staff arriving for early shifts. The parking lot remained nearly empty except for a single luxury SUV that stopped briefly each afternoon. The driver collected mail and left.

Inside, according to billing data, thousands of therapy hours were being logged.

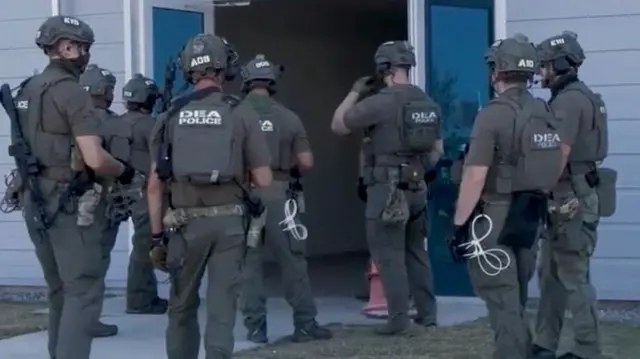

At 6:00 a.m., federal agents executed a search warrant.

They expected to clear examination rooms and offices filled with staff. Instead, they found what investigators later described as an empty shell. Therapy rooms contained unopened office furniture still in boxes. The waiting area had no chairs. There were no patient files stacked on desks, no children’s toys, no sensory equipment.

In the back office, however, server racks were active.

According to court documents, the clinic’s computer system was programmed to automatically generate patient logs and billing entries. Claims were submitted to Minnesota’s Medicaid program for therapy sessions that prosecutors allege never occurred—some tied to children who did not exist, others to real children whose idenтιтies had been used without their families’ full understanding.

The raid on Bright Future was not isolated.

It was part of a sweeping federal crackdown on what prosecutors have described as the largest pandemic-era fraud scheme in Minnesota’s history. By sunset that day, coordinated searches had taken place at multiple sites across the Twin Cities, including nonprofit offices and other health-related centers. Seventy-eight individuals were charged in connection with overlapping investigations into child nutrition and medical ᴀssistance fraud.

Federal officials estimate that, across related schemes, nearly $1 billion in taxpayer funds may have been improperly claimed over a three-year period.

To understand how such a number became possible, investigators point to policy shifts during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emergency measures relaxed oversight requirements for child nutrition and certain Medicaid-funded services to ensure vulnerable populations did not go without food or medical care. The goal was speed and accessibility.

Prosecutors now argue that some individuals exploited that urgency.

The earlier “Feeding Our Future” scandal exposed alleged fraud within the federal child nutrition program, where newly formed nonprofits claimed to distribute millions of meals daily. In many cases, authorities allege the food was never purchased or served. That investigation led to dozens of indictments and convictions.

As scrutiny intensified around meal programs, investigators say elements of the network pivoted to a new target: autism therapy services.

Minnesota’s Medicaid system reimburses significant amounts for autism-related behavioral therapy, a lifeline for families with special needs children. Between 2018 and 2024, the number of licensed autism providers in the state increased dramatically. Payments for such services rose from approximately $6 million annually to nearly $192 million.

Growth alone does not prove wrongdoing. However, federal investigators allege that a subset of new providers were fraudulent “ghost clinics” designed solely to bill the government.

According to charging documents, some clinic operators recruited parents within the community and offered small payments in exchange for allowing their children’s information to be used in billing submissions. In other cases, interpreters and staff listed on payrolls were allegedly individuals who never provided therapy services at all.

The money trail is now central to the case.

Forensic accountants traced millions of dollars from clinic accounts to shell companies described as consulting or logistics firms. From there, funds were withdrawn in cash or transferred through informal money transfer systems commonly referred to as hawala networks. These systems operate on trust-based exchanges and can be difficult to trace once funds move internationally.

Investigators have stated that some transfers were routed to accounts in Turkey, Dubai, Kenya, and other regions. Intelligence agencies are examining whether any of those funds ultimately benefited individuals linked to al-Shabaab, a U.S.-designated terrorist organization operating in Somalia.

Authorities caution that the terrorism-financing aspect remains under investigation and that not all international transfers are inherently criminal. However, if prosecutors can establish that fraud proceeds knowingly supported designated groups, charges could expand significantly.

The case has ignited political controversy.

Republican lawmakers in Washington have accused Minnesota officials of insufficient oversight. State leaders, including Governor Tim Walz and Attorney General Keith Ellison, have denied any intentional neglect and have welcomed federal investigations. Both have emphasized that fraud schemes exploit bureaucratic gaps, not ethnic communities.

Community advocates have also urged caution, warning against collective blame directed at Somali Americans. Minnesota is home to one of the largest Somali diasporas in the United States, the overwhelming majority of whom are law-abiding residents and business owners.

Federal prosecutors stress that criminal indictments target specific individuals and organizations, not entire communities.

In one high-profile arrest tied to the autism clinic investigation, agents detained a clinic director at his upscale lakeside home. Court filings allege he attempted to destroy documents before being taken into custody. Investigators seized luxury vehicles, gold bars, and property deeds both domestically and abroad.

The director and others charged face potential sentences of up to 20 years or more if convicted on fraud and money laundering counts. Additional charges related to international transfers could carry even steeper penalties.

Meanwhile, the fallout has affected legitimate providers. Heightened scrutiny has slowed payments and triggered audits across the autism services sector. Families reliant on real therapy centers report delays and increased paperwork.

The scandal underscores a painful paradox: programs designed to protect vulnerable children were allegedly manipulated for personal enrichment.

As court proceedings move forward, prosecutors continue auditing nonprofit records statewide. Authorities report that some clinics closed abruptly once federal scrutiny intensified, suggesting they may have existed solely on paper.

Recovering stolen funds will be difficult. While agents have seized ᴀssets worth millions, officials acknowledge that a significant portion of the alleged $1 billion has already been dispersed through complex financial channels.

The broader question now facing Minnesota—and other states—is how to balance rapid ᴀssistance during emergencies with robust oversight. Compᴀssion-driven programs can become targets when safeguards lag behind funding.

The glᴀss door at Bright Future Autism Therapy Center now sits boarded up. The servers have been hauled away as evidence. Courtrooms, not headlines, will ultimately determine guilt or innocence.

But the lesson emerging from this investigation is stark: trust without verification can be costly, and the impact of fraud extends beyond dollars—it erodes confidence in systems meant to serve those most in need.